|

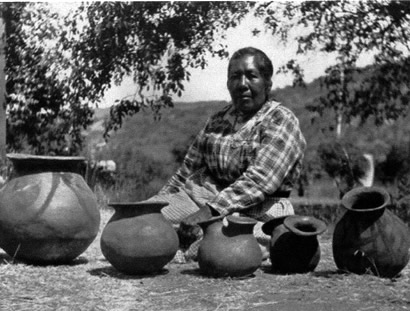

Viejas Elder Maria Alto with some of her pottery. Photo is from the San Diego Historical Society Collection.

Tattered Tidbits No. 18

by Albert Simonson

Front page news this day was a battle at Karlsruhe in the Franco Prussian War and a siege of Strasbourg.

Also front page (“above the fold,” as we wannabe journalists say), was a trip by a survey party from Guatay up to Mount Buttocks. Seriously.

Cuyamaca was in the throes of a big lawsuit over whether Julian mines were included in the Mexican-era Cuyamaca Rancho or were in public land open to mining claims.

The name Cuyamaca refers to “rain beyond,” literally, and the San Diego Union stated that it rained there “almost every fortnight.” The Indian population was by then greatly diminished to 50, but ranchers had 12,500 sheep and 8,500 cattle in the unplanted uplands above Descanso and Rattlesnake Valley.

Cuyamaca [Ah-kwee-amak] was an Indian village situated “in a big pile of rocks” along the road to Stonewall mine. It had been a major village visited by several presidio expeditions and was the scene of an 1837 battle where the Indians held the high ground and cover behind rocks. By 1870, nothing remained but wetlands, rocks, lots of frisky deer, and morteros. So it remains today, but the antelope have been killed off. You can still ride your horse there, and imagine yourself a presidio leatherjacket soldier with a leather shield and long lance and no way to charge your steed in among the rocks to trample those pesky archers.

You can walk through a different Indian village site just upstream of park headquarters along Cold Stream Trail. This was the largest of four villages in Green Valley. The pagan villagers in 1782 greeted presidio soldiers very pleasantly, bearing no arms or, as yet, grudges.

The original name of this village and stream was Ha Pilcha (Water White). The village lay on both banks. The present highway cuts through the outskirts.

Farther downhill is a private campground with abundant water for a pond. Dr. Harper of the Descanso Allison family lived there in 1872 on the Indian site of Parhahui, meaning “The Fox.” Wherever you find a reliable water source and deer, you have probably found an Indian site.

The Sweetwater River runs through most of Cuyamaca. It has had two Spanish names which I have heard, but the oldest name is Indian – “Ah-ha Coo-mulk” (Water Sweet).

One Indian legend tells how this lovely river inspired a battle among the rival mountains, which left Cuyamaca Mountain with a crooked neck. It is still crooked. The asphalt road to the top makes for a moderate hike, with views of wild country. For Indians, this peak had special spiritual meaning. In this way, they were like Minoan and Mesopotamian cultures.

The survey party found that the Indians at the old mission cattle rancho at Descanso had converted to Christianity and so buried their dead instead of cremating them. A bit further east along the coast-to-coast Lee Highway is the site of Hamatayune (acorn bran), long ago corrupted to Samagatuma. There, the survey party found burnt human bones and abalone shells from cremations. There ran the boundary of the Christian world.

Farther north, the survey party came upon the ashes and bones of a recent cremation, that of a woman over 100 years old. She had died on horseback, like gunslinger Jack Palance in “The City Slickers” movie. Her name was Sing-Yu-Ra-Wa, meaning“Woman like the Young Leaf.” Her aged daughter lived at Santa Ysabel with a less vivid Christian name.

There are three mountains on your left as you proceed uphill. The first, with a steep west flank, was called Ipocuiscui, meaning “Straight Up,”or “Crooked Neck,” depending on whom you believe.

The second, past Paso Picacho Campground was Hulcacuis, translated in the newspaper as “The Bunch” (probably a bundle of sticks) or as “Tough-Strong” as the Laguna native Maria Alto said in 1914. She could doll herself up right pretty for a studio portrait, but she still kept her name Kwa-mi-e and all the folklore of her own culture, and passed it on to us. An old saying is,“To say the name of the dead is to make live again.” Now you have her name.

The third mountain, North Peak, with a broad top rather than a “peak,” was spelled Iguai, as was an Indian village on its southeast flank overlooking the broad Cuyamaca meadow and the“laguna que se seca” (lake which dries up).

In Spanish, the mountain was translated to Nalgas, meaning “Buttocks,” or “Rump.”

I don”t quite see the buttocks. Possibly a recumbent expectant mother or a stock market correction chart. You”ll have to look for yourself. It’s not as exalted as the upstart Stonewall Peak, which has a great snaggly lookout on top.

Maria Alto would not have gone for the buttocks concept. She said it was pronounced E-yee, for hidden shelter or den on the mountain where hunted animals escaped their hapless hunters, leaving the hunters perplexed and disgruntled. Or, maybe both versions are alike in a metaphorical Mother-Earth, entering-the-sanctuary, sense.

The Indians, like many cultures, had some proto-Freudian ideas about caves or even small cavities in rock. Such fertility features are known to anthropologists by the Sanskrit word “yoni.” Indians would often enhance the feminine aspects of rock features with pigments and fuzzy plant material until even dullards got the picture. The Lemon Grove off-ramp has some modern luscious ruby red rock lips.

Padre Sanchez happened upon one such shrine in the mountains in 1821. He considered it a “spiritual stumbling block with gross figures and rubbish.” He ordered it destroyed, but it would have been hard for the devout priest to argue that In’ya, the celebrated sun, and females, were not essential to life, including his own, and to the wine grapes he valued so highly.

His own faith could have been considered a “Johnny-come-lately” among older faiths around the world. Maria Alto had a lot to say on solar observance, which dovetails nicely with what archaeologists and holy men in the Andes have told us.

At the winter solstice, a sunrise service was held within dance circles at the summits of certain mountains like Kwuta-Lu-Eah (Song Dance, or Viejas). This was confirmed by archaeologists who documented rock circles and solstitial rock alignments there and at Cowles Mountain. Both sites have been destroyed.

Many tribes in California and elsewhere observed solstices (hilyatai), in the east (enyak), especially the winter ones in December (xalapisu). Padre Boscana in 1826 wrote that local Indians celebrated the winter solstice with more pomp because the sun’s “return meant much to them for it ripened their fruits and seeds. . .and enlivened again the fields with beauty.” It also served to fix their calendrics and was a nice chance for a singalong. To say they “worshipped” the sun would be going beyond the evidence. This benefactor needed no glorification, no recitals, no altars. In’ya gave life, and that’s all there is to it.

I hope, by using these Kumiai words, that we can keep them from being forever forgotten. They link us to a spiritual past and are worth repeating so they do not perish from our mountains.

A scientific expedition in 1736 by a French academy surveyed the equator in the Andes and built monuments at the equator. A more accurate, older monument was later discovered on nearby Monte Catequilla. It was pre-Incan!!

A friend of mine from Hacienda Guachalá was building a new huge monument along the Cayambe road. I yelled to him, “Hey, Cobo, your monument is off by 100 meters,” but he came and grabbed my GPS and did some old Indian trick scrolling down to a different “geodesic datum” or whatever and then my latitude read all zeroes when he handed it back. To which I say, “duh!” He had the advantage of having run three GPS receivers all night long to average them.

The Catequilla platform likewise is exactly on the equator and its solstitial line of rocks is correctly 23.5 degrees, the tilt of the earth’s axis to the sun, like the Viejas line of rocks. This is the exciting world of archaeoastronomy.

In other news, Congressional Republicans were trying to enact an “Income Tax.” The Julian City correspondent reported the McMechan mill was crushing ore from a new discovery called the “Helvetia.” The Cotton mill was to commence crushing 100 tons from the Owens mine.

He concluded, “We expect to make some heavy shipments of bullion this fall.” There was a movement afoot to make Julian City the county seat.

If you prefer more up-to-date news, we can now reveal that Germany won, temporarily, and the court ruled in favor of the Julian miners and that we did in fact get saddled with the income tax.

Further reading: Johnson, Mary E, Legends, etc. (1914), www. quitsato.org.

|