|

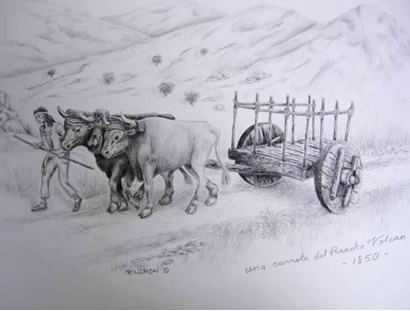

Drawing of Ox Cart by Bonnie Gendron

by Albert Simonson

The 1850 first county tax roll hit our local ranchero pretty hard on his “carretas.”

Both were valued at 50 pesos each, much more than ox carts at other ranchos. They must have been good, sturdy ox carts, with rancho-style solid wheels and extra features like quick-disconnect yoke hitches.

In those days, rancheros and their Indian vaqueros built their own ox carts, which were used for everything from hauling grain to wedding parties to bringing rancho lovelies down to Old Town dances, called fandangos.

The Gastelum family from Ensenada took a trip in one from home to Sonoma on the Camino Real and back. It took them two years and they stayed at nearly every rancho, mission, and presidio along the way. Rancheros were hospitable folk and they enjoyed hearing all the news from visitors. The Gastelums, too, enjoyed the friendly visits.

One thing Rancho Volcan had in abundance was good timber for the massive solid wheels. Usually two or three thick pieces made up each wheel. Also, our Cockney Bill was a good carpenter, in demand as a stage carpenter at the mission theater. Wooden pegs and rawhide held things together.

Spanish carts, in contrast, had world-class spoked wheels, too delicate for our California ox cart roads. There are many variants around the world, derived from Egyptian and Mesopotamian designs. Turkish carts, oddly, have wheels and an axle which rotate as a unit. These are not good on turns, but great on the straightaway. This is a good feature, because oxen annoyingly lunge to the side to snatch roadside grass, but that rigid wheel assembly keeps them on the straight and narrow.

A peculiarity of early California and the rest of New Spain is that the rancheros did not put a contoured yoke across the necks of the oxen. Instead, the straight yoke was tied with rawhide to the horns of the oxen. This is a California solution to the irksome snatching-at-grass problem.

The first ox cart I ever saw was at the Mayan ruins of Iximché in the Guatemala highlands. It was a rumbling, lumbering apparition with gigantic oxen, very high wobbling wheels, and a rawhide bucket swaying to and fro, filled with boiled animal fat for the occasional lube job. Animal fat is not as tenacious as Pep Boys’ grease, but it does permeate the wooden bearings like the sintered bushings in your car. To lube the bearings, you just pull the wooden pin out and wobble the wheel outward and slather the fat onto the axle shaft.

You can still see ox carts at San Miguel Mission and Santa Barbara Presidio. One of the best is in San Diego’s Old Town at the Seeley Stable. It is reported to have been found under a haystack at Sutter’s Fort, where the California Gold Rush began. This is a high-mileage, no-frills , 1806 vintage vehicle with severely worn-down lumpy wheels.

These wheels are among the oldest surviving in California, sturdily built by mission Indians at San Jose. Conchita Ramirez, fleeing wild-eyed forty-niners, rode this cart to San Diego in 1849, taking 3 months to do it with lots of visits along the way. Each wheel is a 5-inch slice of a big tree. Six-by-six timbers form the frame with fine mortise-and-tenon joints, now professionally restored. The wheels had wide treads to reduce wear. It was an ancient craft to build serviceable vehicles with only wood and rawhide, both renewable resources, and little or no iron.

With oxen, the 100% organic tailpipe emissions were minimal, except for greenhouse gas generated by the cud-chewing power source. Still, emissions were way better than an SUV like the Ford Extinction.

Cockney Bill Williams had ox carts at both his ranchos – Volcan de Santa Ysabel (Julian) and Valle de las Viejas (Alpine). We know more about his Viejas carts because Viejas was the major supplier of grain to the army and because a very trusted civic leader remembered Bill’s grain transport. This is how Ephraim Morse described the diorama of his memories to downtown colleagues at the chamber of commerce, as reported in the San Diego Union of 6/1/1900.

“The Mexican ox cart was very much in evidence in those early years. With an ox hide for the bottom and plenty of straw in place of springs, and an Indian driver for the oxen who walked in front as a guide for the oxen to follow, the whole family would pile in. As time was no object with them, the gait of the oxen was quite satisfactory.

In 1853 more grain, principally barley, was raised in the little valley of Viejas than in all the rest of the county. It was hauled in to Old Town, over a wild, broken country without roads for more than half the distance. Only Mexican carts, which by the way were built on the ranch, with their solid block wheels, drawn by oxen, their yokes lashed to their horns, could be used on such a trip. Long stretches of road, then first opened by those primitive trains, are now traveled daily on mail coaches. The grain brought 3 cents per pound.”

Morse said the ox cart road from Cockney Bill’s Viejas Rancho went through “Mesa del Arroz” or “Grassy Mesa” around Alpine’s middle school. At the eastern edge of the open space preserve, two trails split off from the road which continued past the present school to “Secuan” (Sycuan) and Rancho Jamacha, the only house along the road.

A good watering stop was the spring at San Jorge, which can still be seen in museum grounds at Bancroft Drive and Memory Lane in Spring Valley. The road then followed Chollas Creek along present Route 94 to what is now San Diego’s downtown.

Another important ox cart trail connected Old Town with the ship landing at La Playa, Morse added.

At the time of his speech, the retired Morse and his wife lived near the old road, at the present intersection of Tavern and South Grade in Alpine.

In about the same year, a Conejo Indian described how it was to harvest Bill’s grain crop when he was a boy. Although “Old Leno” had worked at Viejas, I think it is safe to say that grain harvesting at Rancho Volcan was similar.

“We worked, all of the Indians, from the first light of day until it was too dark to see the grain any more. The days are very long in summer, and we had no water except what the young squaws would sometimes bring to us, though of course they had to work too. We had a small canvas apron on the front of us, and we reached out and pulled the grain toward us and we cut it with a reaping hook and piled it, and the sleds came through the fields and picked it up - and all day and every day we worked so for many weeks. And the pay was fifty cents a day. But the land was better then than it now is and we did not have to bend down to the grain.”

With grain at 3 cents per pound, Leno’s pay was not so bad, and he could even aspire to buying a ranchito if he were so inclined.

It is noteworthy that around 1900 the fertile soil was already less productive. Old Leno also described severe flooding, which he attributed to spirits angry at the ways of man. Perhaps he was thinking about shortsighted land management, remembering when the bottomlands yielded 3 crops a year.

The heavy rains of 1916 were the worst in history and the agricultural potential of both Viejas and Volcan valleys, like many upland meadows, was finally destroyed by gullying.

Today, both of Cockney Bill’s ranchos can serve as examples of environmental devastation’s economic costs.

Oxen had a long run as man’s power source. A three-oxpower Minoan cart model has been unearthed in Crete. Ancient Byzantium dominated the Bosporus Strait, which in Greek meant ox crossing (bous-poros). The university town of Oxford arguably means just that – an ox ford, hence a strategic spot.

After Bill left Volcan, his English successor continued to cultivate grain with other draft animals, but new Volcan neighbors still used oxen. Bill kept nine “yokes” (teams) of oxen at Viejas in 1860, according to an agricultural survey.

Younger readers may not know exactly what oxen are. They are not born as little oxlets. Young bulls are afflicted with the same vexatious behavioral aberrations as teenage boys, owing to testosterone saturation. Luckily a firm hand and a time honored surgical procedure bestow the blessings of lasting equanimity and contentedness.

Both Californios and Yankee emigrants came to love their oxen on overland journeys. They were slower than horses or mules, but gifted with plodding strength, calm nerves, and an ability to survive on scant forage.

Ox carts are still a popular feature of traditional Oaxaca parades. Their oxen wear garlands of bright flowers draped over their heads and yokes. Less festive for the oxen is the power steering feature – slender reins tied to their nose-rings.

Just think if we had a team of oxen and an ox cart wobbling and rumbling along in one of our parades, with some eminent citizen seated regally on a buttock-embracing heap of straw over a rawhide floor. . . .

|