|

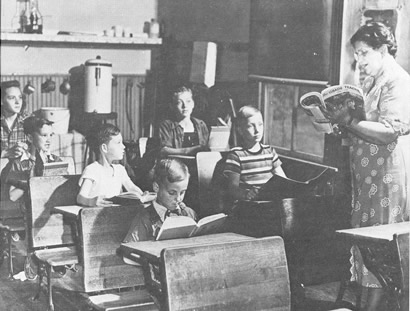

A typical one-room schoolhouse classroom.

by Vic Head

Hazel Taylor, “the girl who sat on a wildcat,” [another story for another time] was married, now Hazel Hohanshelt, and taught us at the Alpine School, 30 miles east of San Diego. We were 25 kids scattered through eight grades. A brilliant girl, she was very young when she served as our teacher. Her youth showed when, after being told by the school board what she might wear, she announced to us, “I don’t care what they say, if I want to teach school in a bathing suit, I will!” Of course she never did. She had a ukulele and taught us the three basic chords and quite a few songs. The laughable “Ivan Skavinsky Skavar” and the hauntingly beautiful song by the last native ruler of Hawaii, Queen Liliuokalani, “Aloha Oe” are among many I remember after 67 years. For a few minutes a day she read aloud from great books and how we thrilled to Mark Twain’s Tom Sawyer and often cringed a bit at the sequel, Huckleberry Finn!

We had no homework. The whole school drilled the addition and multiplication tables, clapping hands and rhythmically reciting—seven times six equals forty-two, seven times seven, etc. No, eighth graders did not feel insulted—we were helping the teacher to drill the little kids! In a back corner of the room were six unassigned seats where each grade would go with the teacher to recite history and geography while pupils of other grades stayed in their regular seats and studied their assignments.

The wooden structure of the schoolhouse sat centered in a four-acre fenced-in yard with a dozen eucalyptus trees at the south end, and a totally bare adobe surface otherwise, well packed by many bare feet, and easy to mark off for games. Fifteen minutes of morning recess and a full hour for lunch and games were unsupervised, older pupils learning responsibility in teaching games and fair play to younger. The girls and younger boys had their hopscotch, jumprope, see-saws, swings and slides, or the sing-song games like “Here Comes a Duke a-Riding.” The boys had marbles, which I learned to my sorrow were played “for keeps” since I had no money to buy more, baseball with a ball wound from rubber strips cut from innertubes in ¼ inch width and stretched tight, mumblty-peg which taught respect for sharp knife blades, kick-the-can and other variations of hide-and-seek, and field games like capture-the-flag or the favorite, calaboose, which involved crossing a line to capture an enemy by running around him and back without being tagged, or rescuing one of your own who had been so captured and had to sit in the enemy calaboose until tagged by one of us. I remember being pursued by five opponents for many minutes, unable to dodge back to safety, until I collapsed on the adobe and cried—but none ridiculed me, for I had rescued another of our team.

Two desks and a wide seat for two pupils were held together by a cast-iron frame. These came in two sizes, smaller in the front near the teacher’s desk. There were two hinged desk tops below which were kept books and papers. There were two glass ink wells fitted into holes to prevent spilling, and long grooves for pencil and pen. The temptation to whisper to your deskmate was always strong, but Hazel was tolerant and if she had to stop a tête-à-tête for lasting too long, we felt shame rather than resentment. But it was not always so. Back when I was in third grade the teacher was Mr. Beadle, liberal with the ruler on the knuckles of miscreants. He used to stand in the back of the room during study periods and sneak up behind a whispering pair and seize the hair of each in each big hand and knock their heads together with impact audible throughout the school.

From Alpine we could see a skyline of mountains dominated by the bare rocks of El Capitan with fringes of white which we were told was something called snow.

Some of the luckier kids lived in families that owned automobiles and had been driven up to where they could run and slide on their shoes. But to most it was a distant mystery until one day in the midst of a downpour we could see a few white flakes among the raindrops. “Look at the snow coming down, “Hazel suddenly called out and then she utterly lost control as we rushed out. Oh, she was right out there with us getting soaked to the skin trying to catch snowflakes but having them melt on our hands so we never got a good look.

Three or four miles east was another school intended for Indians, but my sister, who lived on a ranch much closer to it than to Alpine, used to ride a pony to the Indian school. Sometimes there were athletic competitions between schools, but they were a joke. The Indian pupils averaged several years older than we, and clobbered us in running, jumping, dashes, and as I particularly recall, volleyball, where six-foot Indian boys held us scoreless.

A Franklin wood stove stood in a central aisle for use on a very few frosty mornings, and it was fun when Hazel let us shape tiny pots or animal figures of the plentiful adobe to leave in the dying embers until baked to a beautiful brick red.

Between teacher’s desk and blackboards was space to practice the Virginia Reel and, oh joy, fifth grader Patty was my partner. But when we were to do a public evening performance at the Alpine Tavern, the only hotel for miles, I was forced to drop out because home was 1 ½ miles across roadless terrain which was out of the question for me at night.

I had missed a year after third grade under doctor’s orders to run wild in the country, but breezed through fourth with so much help from Hazel that she saw fit to promote me to sixth without having to ask permission from any higher authority.

Twenty years later I visited Alpine. They had picked up the schoolhouse with a crane and placed it in a south corner of the yard for use as a maintenance shop, while most of the four acres were filled by a monstrous brick building for 300 pupils. Hazel was now the principal, where before there had been no principal. “Where on earth did you get 300 kids in this little town, even in 1949?” Hazel confessed to considerable trepidation over the move toward centralization. Some of her pupils from eastern San Diego County had to spend four or five hours on a bus each day! And she deplored the total separation of grades and the loss of the lessons in responsibility that had accompanied multigrade interaction.

In 1929 my family moved from southern California to a country family homestead in Hopkinton Township, New Hampshire, which had seventeen one-room schools scattered over many square miles. That is another story, except to say the “Main Road School,” a mile walk from home past seven other houses, had only ten pupils scattered through eight grades. When I arrived for my first day as the only pupil in seventh grade, Miss Blake sent me home with the warning, “Don’t come back without shoes on!” My mother had planned to save enough to buy me shoes by the end of October, but now she had to swallow her pride and borrow from a neighbor to cover both shoes and busfare to go buy them. Two weeks later the school superintendent visited. Miss Blake: “What do you think of a little boy who comes to school barefoot?” Superintendent: “Why, I don’t know, I used to.” I never knew how parents teamed up behind the scenes, but six weeks later Miss Blake was gone and I did seventh and eighth grades with a cross-eyed angel.

|