|

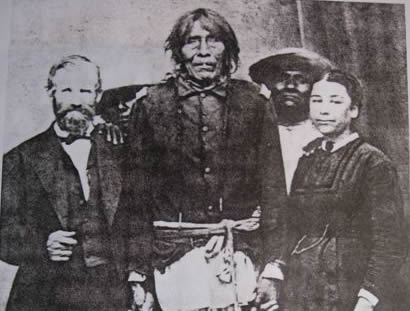

Chief Pascual and The Jaegers

By Albert Simonson

It has been said by those who contemplate such issues, that the West was conquered by mules. Men were carried along and were useful for finding forage and water. Up north, Bishop pays tribute to this noble blend of ass and horse during Mule Days when many hundreds pass in review before admiring crowds.

Let’s say you were a muleskinner on the well traveled freight road between Warner’s Ranch and Santa Ysabel. A good place to wash down the road dust from your parched throat was the “grog shop” in Carrizzo Meadow, 4 miles north of Santa Ysabel’s old mission buildings. The grass is still a mule’s Garden of Eden.

You would not want to create an impression of a greenhorn or bullwacker as you pull up in front of that worthy gringo successor to a rancho “cantina” or “pulquerîa.” Pulque is undistilled tequila, the fuel of early California vaqueros, those leathery prototypes of hardfisted Hollywood he-men.

For Indian vaqueros, the grog shop was conveniently near the village of Ajata, midway between Mucucuiz (near Santa Ysabel) and Tawee (Monkey Hill by Lake Henshaw), on the wagon road a half mile north of Ludwig Jaeger’s houses, down toward the present junction of highways 76 and 79.

Bullwackers drove ox-teams. These guys could never achieve the professional panache of a skilled muleskinner. In early times their job was done by a single Indian plodding along in front of the pair of oxen, hopeful of promotion to bullwacker status.

The castrated oxen were slow but steady, easy to handle, beloved of women, and did well on poor forage. Horses were fast but finicky like cantina fillies. Mules were just right, the muleskinners felt, and smarter too.

I remember fondly a festively attired Greek mule, Homer, who carried me high up above the sea one morning. Later that evening, in the setting sun, he saw (or perhaps smelled) me among countless others walking down to the sea like all the days of his life.

His personal greeting to me was startling, something between a bray and a neigh. I think it was both discerning and heartfelt, a fitting salute to the millennial bond between man and mule. We are both Darwinian improbabilities, freaks, you might say.

What we creatures all have in common is greater than our differences. The opening of the American West was a giant leap for mankind and mulekind alike.

Teams of eight mules or more oxen were not unusual in the West. To make a dramatic approach to the grog shop, you had to manage your mules with a single jerk line to your lead animal on the near (left) side. You sat astride the near side wheel mule.

You could increase your charisma with a sonorous yet melodic voice and a command of mule vocabulary, in concert with sparing but emphatic snapping of your blacksnake whip, all accompanied by a basso continuo of animal snorts and gaseous reverberations. The aft lard bucket swayed to and fro, marking like a metronome fleeting moments of life between dead yesterdays and unborn tomorrows.

Properly executed, your arrival at the grog shop could be like Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9, rising to a dramatic crescendo. Instead of a conductor’s baton, you conduct with the jerk line running forward through “hame rings.” The lead pair has hame bells tinkling your approach while Indian boys run alongside all excited.

Any mistake, though, and it could sound like a post-Wagnerian “Entry of the Cops into Mulvaney’s.”

Vocabulary is important. “Gee” means go right. “Haw” means go left. The correct tug on the jerk line to the lead animal stops or steers the whole procession [steady left, jerk right]. Then you can stride manfully into the cool of the grog shop with its assembled vaqueros and greasers (axle lubrication technicians).

Jaeger was respected, too. He had established the ferry and emigrant emporium at Yuma Crossing. This storied celebrity now lived uphill from the grog shop, and used Santa Ysabel Rancho to support the business.

Famously, he once rode all the way from the Colorado River to a San Diego doctor with a Yuma arrow in his neck, like a weather vane on horseback. You have to admire that.

Jaeger (pronounced “Diego” by the Indians) ordered a survey of the rancho. The field notes of the Leighton 1856 survey give us the locations of the grog shop, Jaeger’s house and other buildings.

The term “muleskinner” does not insult the mule. On the contrary, it means to fleece or outsmart an animal more clever than stubborn. This can be a challenge for us greenhorns or [groan] city slickers.

Harnessing is a challenge, as well, with long teams and a ton of freight per mule. This is best done by a professional “swamper”, especially when hauling valuable boilers and explosives to Julian mines, up the Coleman Toll Road.

For a swamper to be promoted to skinner, he has to learn the correct intonation of the giddyup command. “G’long, hup there!” A really good team rewards you then by smartly stepping out in unison like a Spartan phalanx marching on Athens. On turns, inside mules stepped over the trace chain and drew sideways.

Only the pointers, mules addressed by name, carried out this amazing feat of multitasking and sidestepping, which made a curve in the chain. Intellectually, this surpasses dressage horses and my wretched attempts at square dancing.

Any variation in the steady klumpf, klumph hoofbeat signals a warning to a trained ear, as one false note in that ninth symphony would grate cruelly the ear of a conductor.

You can learn mulespeak at the Seeley barn in Old Town. There you will find an oxcart, a heavy freight wagon, and the actual “mudwagon” (light coach) used on the San Diego – Fort Yuma route through Santa Ysabel and Warner’s. A spur line, still visible, ran later up to Julian from the Santa Ysabel Inn (next to the store) up the Coleman Road.

Albert Seeley had an 1874 Wells Fargo contract and Chester Gunn was our ticket agent. Chester lived at “Summit Ranch” where the windmill on Farmer Road now stands in a flat once brimming with fruit trees. Nearby is a historic large horse barn of stone.

The mudwagon is an unrestored original treasure. Merely to smell its stained floorboards is organic aroma therapy.

Readers may take umbrage at my earlier use of the word “gringo.” This is a nonjudgmental term cheerfully adopted by Anglo readers of the Gringo Gazette south of the border.

An article in that paper traced the G-word to an 1849 journal of the Audubon emigrant party. They overheard the muttered word as they came ashore at Veracruz, bound for gold country via our Banner Canyon and Santa Ysabel Creek.

Language is an unfolding multifoliate rose, now comforting, now mysterious, always instructive, but nothing to quibble about.

From Major Heintzelman’s 1851-3 diaries, we see that army wagon trains used mules. He and the express riders usually rode mules. During Indian campaigns, they and teamsters camped at Santa Ysabel’s creek. They were men of high moral standards; one was hanged for stealing a saddle.

After the arrival of the railroad, army freight traffic was replaced by mine traffic on the old wagon road to Santa Ysabel and also on the “Camino de la Sierra” through Cuyamaca.

To jaded mules, though, it must have seemed like the French witticism, “The more it changes, the more it remains the same.” But nothing was forever in the drama of mules and men.

Author's Note:

This writer’s article might seem more worthwhile if you try re-reading it while listening to Jimmie Rodgers in 1930 yodeling “Mule Skinner Blues” on YouTube.

|