|

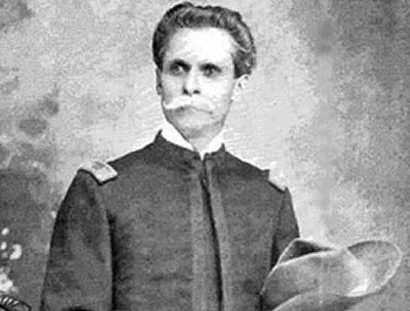

Captain Harry Jeremiah Parks

Photographs

February 14, 1848 - October 19, 1927

by Vic Head

The Congressional Medal of Honor is the highest military honor awarded by the United States for “uncommon valor” in action above and beyond the call of duty in combat against an armed enemy. As of the end of the Vietnam War, a total of 3,418 such medals had been awarded, nearly half of them during the Civil War. So what makes Captain Parks so special? First, few indeed were personally awarded in a face-to-face ceremony by President Lincoln; second, he was only sixteen years of age when the award was made.

I was privileged to be befriended by Captain Parks when I first moved to Alpine, California in January 1926, when I had just turned eight years old and the Captain was a month shy of seventy-eight. He was living in a tiny cottage some called the “Doll House” down the hill and across a creek from old Highway 80 and behind the famous Log Cabin Café owned by the Foster family.

Captain Parks told me how proud he was that throughout an illustrious army career spanning more than four decades he had never killed a man. As a child I was intrigued by his curved sword, which would slide just as easily into and out of its curved scabbard as would a straight sword with a straight scabbard. He called it a saber. He had a guitar leaning in a corner that he said sometimes gave out spontaneous music in the wee small hours.

My parents were divorced when I was a baby (1918). In 1926 my mother was the third librarian in the new Alpine Library, and Captain Parks befriended her, sometimes driving her around 30 miles each way into San Diego. She never tired of telling what an expert driver he was. Once when a child dashed into the street, he avoided catastrophe by driving onto the sidewalk. Though he was twice her age he, perhaps in fun, proposed marriage.

Note: Vic Head has shared many of his memories of Alpine with the Alpine Historical Society’s Barbara Cater. The preceding article is among these memories. Barbara met Vic through Patty Heyser when Patty asked the Historical Society to provide assistance to Vic in his research of Captain Parks. Since that time Barbara and Vic have kept in touch. He continues to send her his wonderful articles about Alpine.

Currently residing in Pennsylvania, Mr. Head reports the following regarding his research projects and the photo shown below: “Photo courtesy of Patty Heyser, formerly Patty Foster, whom I worshiped all unbeknownst to her in fifth grade in the one-room schoolhouse in Alpine. Now that we are both 88 years old, Patty and I are in frequent communication and she and her family have been very helpful in tracing Captain Parks’ later life. Another invaluable source has been a search of the National Census records to learn where Harry J. Parks was to be found every ten years. This was conducted by one of Alpine’s younger residents, Barbara Cater, who is active in Alpine’s Historical Society.

I am also particularly grateful to Roy Williams who provided 16 pages of backhand script in his mother’s writing, which Captain Parks had allowed her to copy from his diary and correspondence. Roy was second cousin once removed to our beloved teacher Hazel Hohanshelt and took care of her correspondence in her old age. Hazel died on August 20, 2004, at the age of 98.”

Harry J. Parks was born February 24, 1848, near Orangeville, New York. He enlisted in Company A, 9th New York Cavalry and served until the close of the war. He is one of the very few who had the honor of having his medal placed upon his breast by the President himself, and when Lincoln did so he embraced the young soldier, then but sixteen years of age, and said, “God bless my boy hero of the Shenandoah,” and directed that he should have twenty days’ furlough. Which of us would not glory in having a memory like that, of Abraham Lincoln, the greatest American since Washington. The circumstance that gave young Parks the opportunity of thus meeting the President was, that after capturing the flag for which he gained his medal, General Sheridan ordered him to take it to Washington and present it in person to the War Department. The manner in which the boy captured the flag was one of those acts that shows the dash and utter want of fear exhibited by the young boys who formed so large a part of our army. On the evening of October 19th, when the last charge was made by our troops and the enemy driven back, broken and routed, our cavalry started in pursuit and Parks, rushing ahead, got far in advance of any of his comrades. Finding himself among many Confederates, he singled out one who carried a flag over his shoulder. Riding up to him he said, in a voice of authority, “Give me that flag.” The man wheeled and fired at him instead. Parks promptly returned the compliment and the color bearer answered, “I surrender,” handed over the “Bonnie Blue Flag” and was marched to the rear. Meeting some of his comrades, Companion Parks turned his prisoner over to them and galloped to the front again. Encountering three teams trying to get away, he rode up to the leading driver and ordered him to turn quietly and follow him. Mistaking young Parks in the darkness for one of their own people, he did so, and the three teams and their drivers, including four soldiers, were conducted in to our lines. The wagons were found loaded with cigars and luxuries for headquarters and were very acceptable. I quote from a letter of Capt. A. C. Robertson, who commanded Co. A, 9th New York Calvary during the war:

“H. J. Parks served in my Co. A., 9th New York Cavalry and was under my immediate command on October 19th, 1864, and I was personally known to him. I am pleased to state that his conduct on that day was not unlike that of the more than a year and a half in which he served under me. Had there been a flag at the end of each of his soldierly actions, the return of them to the states whose troops bore them in 61-65, the number would have been greater than they are now. At the breaking out of our Spanish War, Companion Parks organized a Light Battery, a Colorado Artillery, was commissioned captain and served until the end of the war, and while at Fort Hancock in command of this battery, he served as Judge of the Military Court. When the battery was mustered out, the members presented him with a diamond-set medal. Previous to the Spanish War he commanded a Light Artillery Battery of the Colorado Guards, and the members presented him with a gold mounted sword of honor. The state of Colorado also presented him with a medal for valor and patriotism. Companion Parks has willed his medal to his nephew, Prof. Charles A. Wheeler, of Connecticut, having neither wife nor children.”

by Harry J. Parks

By request of the War Department for a statement of how I won my Medal, I herein make a sworn statement of the same.

On October 19th, 1864, during General Sheridan’s famous battle in Shenandoah Valley when a great defeat of the Union forces was turned into a grand victory for us in one day, the Confederate forces were stampeded and while retreating, my company [Company A, 9th New York Cavalry] was ordered to follow the enemy and capture all we could of them and their wagon train.

During our hasty charge we reached Strasburg and had just about reached the rear of the enemy’s wagon train when darkness came on. Quick work had to be done, it being only three miles to Fisher’s Hill. This being the enemy’s old breastworks, they were sure to rally on this hill which they had left in the morning.

My Captain, knowing I had a lively horse, said to me, “Harry, you are brave. Make a dash ahead, stop all you can of the train.” At once I was on the jump. Leaving the road, I took to the valley, pushed forward rapidly. Darkness favored me. While passing many straggling soldiers, I ran into a color-bearer. Halting him I ordered him to hand me the flag and coat. At once he fired, ticking my ear. Then he sprang behind my horse and ran for the river near by. Returning my saber to its scabbard and drawing my revolver I dashed after him, firing at him whereupon he threw down the flag and said, “I surrender,” handing me the flag and coat. I marched him back to our men, then galloped forward again until I was near the Stone Bridge at the foot of Fisher’s Hill. Here I stopped and slipped on the coat; then halted the train, taking charge of three of the wagons, ordered them to turn about and go back into camp. Taking me to be an officer of their army the drivers obeyed. There were rebels all around us so I let them think I was one of them.

Starting back I saw two soldiers sitting by the roadside. I said, “Boys, you’re tired. Put your guns in the rear of the wagon and get up in front and ride.” They seemed glad of this chance. Going a short distance further I met two more men, served them the same way, placing two in each wagon. Soon I informed them they were all prisoners. One of them said, “Who in hell are you anyhow?” I said, “You’ll find out if you try to leave the wagon.”

Arriving at our Army Camp and the wagons parked, I gave the men my hand and said, “Well, boys, you are on the right side now, so be good and you’ll be happy.” They all seemed pleased. One said his wagon contained groceries, cigars and other things for the officers, I think he said of Kershaw’s Headquarters. This was good news to me. At once I planned to get part of those stores. I called out “Is there anyone here from Co. A, 9th NY Cavalry?” From out in the darkness an answer came, “Yes.” Well, we got busy and quickly filled two foraging racks and strapped the same on our horses. Soon the guard came taking charge, and we hurried off to our Regiment which we found in about an hour in camp, sleeping. We turned in, not having had anything to eat for twenty-four hours. The next morning I informed the Captain of my good luck. He sent for Colonel Nichols. Then we all sat down for a feast from my goods captured and finished on the cigars that were passed around. So far I had said nothing about the flag. When I uncovered it, holding it up, the boys cheered. Taking me by the hand, the Colonel congratulated me and told me to keep the flag while he reported the same.

Early that morning General Torbert started me up the valley with our Division to learn the location of the enemy. Meanwhile he had sent an order for me to report to him with the flag. When he saw it he inquired where the staff of the flag was. I told him I had stripped it from the staff when captured. He told me to find something to fly it on. At a farmhouse I found an old rake handle. Tying the flag to it, I hastened to the head of the marching column, cheered by the men along the line. The General was pleased with my success and had me take lunch with him at noon. That evening we returned to the Army. Soon an order came from General Sheridan for me to report to him with the flag, prepared to go to Washington.

When I reported, the General said he had learned of what I had accomplished and spoke in praise of my act. Said he would send me with General Custer to Washington to report to the War Department. With an escort of Cavalry we traveled all night, reaching Martinsburg the next morning, and took a train for Washington, arriving there in the afternoon, too late to report.

The General requested me to meet him at 10:00 a.m. Monday. This was done. We started for the War Department. The people all around us wished to carry us on their shoulders. Many followed to Secretary Stanton’s office. Here we were kindly received and after the greeting of General Custer, I was introduced with the flag. Stanton’s first words were, “Well, the boy has the Bonnie Blue Flag, the first to enter this department.” It was all blue field with two rows crossing of large white stars.

When introduced an officer stepped forward speaking in my behalf words of praise at a request from my Colonel. It was a surprise to me. Then Stanton took me by the hand saying I was deserving of great credit, and wished if the war lasted I would rise to the rank of my superior officer standing beside me (meaning Custer). He then informed me that a medal of honor would be given me with a furlough for twenty days and a hundred dollars and transportation home. I was also informed that I should remain in the city for four days obtaining a pass to see the city while the medal was being made.

Strolling around seeing the city I wandered into the White House. The guard noticed me and my worn out clothing, inquiring if I was from the front. I handed him my pass. He seemed surprised and said, “Stand here a minute.” He left, and returned shortly saying, “The President wishes to see you.” My heart bounded with joy. When I saw Lincoln both hands were extended to meet and greet me. He said many kind words and requested me to come in when I received the medal as he wished to see it. Upon receiving the medal I went at once to see the President. Again he received me kindly, with a smile on his manly face. He took the medal from the case and pinned it on my breast over my throbbing heart. Then placing his arm around me he said, “God bless my hero boy of the Shenandoah.”

I was then only sixteen years old. The President Abraham Lincoln had won my love and admiration. He was more to me than the Medal of Honor.

HARRY JEREMIAH PARKS

Death certificate #1728 – San Diego, CA

Died: Naval Hospital, San Diego

Date of death: October 19, 1927

Was in the hospital October 1st – 19th

Cause of death: Carcinoma of esophagus

Widowed

Occupation: Retired Rancher

Birth Date: February 24, 1848

Birthplace: New York

Father: James Parks – Pennsylvania

Mother: Rachel White – New York

19 months in Alpine

14 years in California

Place of burial: Arlington Cemetery

Washington, DC

Section ES Site 1200

Buried: October 23, 1927

Undertaker: Davis-Bonham Mortuary

1752 4th Street, San Diego

Embalmment Lic. #1796

|